Hello, ImmunoThoughts’ readers, welcome to our first interview post! I have to start this post by saying how extremely fortunate I am. I was very lucky to have an amazing mentor for the past 5 years. For me, there was not a doubt about who would be the first person I would like to interview for my blog. These interview posts have two very specific goals: (1) to share current immunology research using accessible language, and (2) to share advice to undecided/ young scientists. But really, after reading this post I hope we can agree that the advice presented here can be applied to anyone.

Without further ado, it is with great pleasure that I present to you, Dr. Martin J. Richer. Thank you, Martin, for taking the time to share such amazing insights with the ImmunoThoughts’ readers.

Martin and I at the Candian Society for Immunology Meeting, 2019 – Banff, Ab.

The journey to becoming a scientist

I think that most people believe that to become a scientist, you have to follow a very straight path. But we all know that there is a lot behind what our CV shows, and for Martin, this was not different. Martin grew up in a small town called Lachute, which is located one hour away from Montreal, QC. His family, most of who are/were educators, promoted an environment where curiosity and education were very important.

A memorable book Martin read when he was still a kid. It talks about the life of Louis Pasteur.

“I didn’t really know exactly what I wanted to do growing up. I did fairly well in school, and I did love science. But, at least when I was growing up, I really thought that the natural path when you do well in school is to become a lawyer or a doctor.” He explained to me that his original goal was to become an MD. However, after he did not get into medical school, he started an undergraduate degree in Microbiology and Immunology at McGill University. “I was seeing this [step] more as a premed degree and I didn’t really think it would become my career and a lifelong pursuit”. Although he admitted that he did not know much about the program, he agreed it sounded very interesting.

Martin recounted that he was “very lucky” on his career path. He explained that he had the opportunity to work in a lab during the first summer as an undergraduate student. Since he had no previous research experience, he claimed that he “did mistakes after mistakes”. “I’m sure that my work did absolutely nothing to help the lab, but this experience taught me that I really liked scientific research and the curiosity behind it”.

Martin then started his honours research project with Dr. Michael DuBow. “I loved the atmosphere of the research lab. Michael was really demanding but he really taught us to care more about the data than trying to impress him”.

As he continued explaining his career path, Martin touched a crucial subject, which I believe has crossed many of our minds. “It is very hard to know what you want to do. Even though I grew up in a very educated family, no one was a university professor.” He told me that most of the time as an undergraduate student, we look at the professors and know they are teachers. Unfortunately, many of us don’t have the opportunity to see their research side so we don’t really understand what the position really entails.

Martin went on to do a master’s degree, although he admitted that, “frankly, I wasn’t sure that research was the right fit for me at the time and, to be honest, I didn’t work hard enough and I didn’t understand the effort that was needed to be successful in research”. So then…

“I quit science. Forever. I was walking away from it!”

After this moment (which I am completely sure many of us have stumbled into), Martin decided to take a year off and travel. He learned a lot about himself and after a year abroad he knew he needed a job and the only training he had was in science. Martin stated that “he got really lucky” and was accepted for a technician position in the laboratory of Dr. George Spiegelman in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology at The University of British Columbia, in Vancouver.

“George is the reason why I am still a scientist. George was one of the most influential people, among many, in my career”. With a big smile, Martin told me that one day, Dr. Spiegelman came to talk to him and he said: “our job as academic scientists is to generate questions and not necessarily to generate answers”. This very “out of the blue” conversation completely changed how Martin started to view science. He emphasized that science is difficult because most of the time we don’t get the answers we are looking for, but if we are looking for questions, it is a different story. This was the moment that made Martin decided to continue with his scientific studies.

As Martin continued to describe his career path, of doing a PhD at The University of British Columbia and postdoctoral training at The University of Iowa, there was not a single moment in which he forgot to acknowledge the contribution of his past mentors. Dr. Marc Horwitz, Dr. John Harty, Dr. Ninan Abraham were just a few of the names mentioned by him.

It was truly incredible to hear about how each of his mentors helped shape his career. “I would not be here without my mentors, that is very, very clear. I try to thank them as much as I can and I never will be able to do it properly. So, the only thing I can do is pay it forward”.

Martin became an Assistant professor at the Department of Microbiology and Immunology at McGill University in 2014 and has continued to work on amazing research projects since then. And, as a side note, I can take the lead from my lab mates and say that without a doubt, Martin has truly paid it forward!

Could you explain to us your scientific research in a very accessible way?

“The work has evolved a lot which is also part of the fun”. Martin described to me how much his research has changed since the start. “In my PhD studies, I started to work with viruses that cause autoimmune diseases, which is when your immune system rather than protect you, actually turns on itself causing disease. It really fascinated me that some of these infections, which are easily dealt with by the immune system, can actually send signals to the body that makes it turn against itself”. But how does it actually work? That was the question he started to ask at that time. Yet, in order to answer it, he needed to understand the basics.

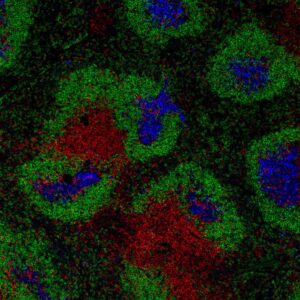

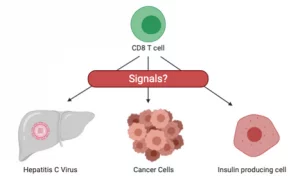

He decided to focus on understanding the mechanism of function of CD8 T cells. “I became fascinated with these cells called cytotoxic T cells, or killer T cells, and their job to kill infected cells”. Although in many cases these cells work just fine, if they recognize the wrong cell, or are told the wrong signal, they can turn onto the cells of our body causing disease. He continued to give an explanation of this process in Type I Diabetes, which occurs when CD8 T cells kill our insulin-producing cells in the pancreas.

“How these cells work? What are the signals that tell these cells that is ok, versus not ok, to respond?”

If you remember from my last post, I mentioned that CD8 T cells need to be activated to start working. Martin became interested in the ability of CD8 T cells to become activated with a very little amount of what they need to recognize. “CD8 T cells are specific for this one piece of this one virus, and they need to be able to find a tiny little amount of this” to perform their function in time to protect an infected person. Martin proceeded to explain that he started to explore the signals that made CD8 T cells respond very well and some that impaired their response.

“Why do we have HCV [hepatitis C virus] that stays in the body, maybe, forever? Why do we have cancer, where the CD8 T cells should kill the cancer cells, yet they don’t? Why do we have diabetes, where CD8 T cells shouldn’t be killing our own cells, yet they do?” This is the global vision of his lab, to understand how T cells are regulated by different external signals. Signals that tell them what do to, when to do, and how to do it properly.

Image created with BioRender

“I’m a really a basic scientific researcher at heart. To me, it is a little bit like being a mechanic. Maybe you will get lucky and fix a car without knowing how it works at all. But, it is easier if you know how it works and some of the mechanisms of what makes it go wrong”.

Martin admitted that our ability to take a very complex situation and try to understand how it functions is amazing. “This is the beauty of academic science. No one is telling me I need to make a drug for X or Y, my job is to generate questions! This goes back to what George told me. Everything we do, if it is generating more questions, we are doing our job. That is why it is so fascinating. We will never understand everything, there will always be something new, something we don’t know and that is why this is so fun”.

I think that we can all agree that your job sounds marvelous. But tell me, who exactly can be a scientist?

“First of all, everyone can be a scientist”. Martin believes that you don’t need to be born in family X, to become a scientist, “as long as you are curious and you want to learn” you can do it.

He affirmed that in a way, we are all scientists at some point in our lives. As kids, the little observations we make such as looking at leaves and bugs, is science. But many times the problem comes at the transition from undergraduate to graduate school. He stated that our education system focuses on teaching about things that we know, but as soon as you switch to graduate school everything is different. At this stage, we start to focus on the things we don’t know, and it can be hard on many students. “You have to be humble enough to know what you don’t know”.

“The other big advice for a young scientist is to just do what you love”

Martin then touched on a subject that can trouble many students. We are constantly hearing professors worrying about funding, and about how competitive research can be. But Martin enlightened me by saying: “Follow your passion, work on what you love. If it happens to be the hottest cell type right now that is cool, but if it is not, who cares, just push and follow the data! As long as you do good science it will get recognized”

“Be willing to be interested in something, be willing to fight for it, but also be willing to be wrong”

Just like any other job, being a scientist can be very hard and we shouldn’t try to mask that. Days can be quite long, experiments might not work, but it is all about taking a step back and learning from your mistakes.

“When you do an experiment and it doesn’t fit the result you expected, your first reaction is probably to put it aside. But much of my research program has been based on experiments that somehow killed another idea”. Martin has been taught by his mentors to look at the data and see what it is showing to you. “Yes, it is telling you that you are wrong in some ways. But most of the time, it is telling something more! The willingness to recognize that ‘Hey, this is different!’ is an important part of pushing research projects forward”. He continued to affirm that you are not wrong, you are just developing more questions to be answered. “This is what makes this job unique!”

Of course, not everything is always easy when you decide to pursue a career as a scientist “Yes, I complain about a lot of things of this job. It is a difficult job, there is a lot of demand on our time. It is a stressful and competitive field. But at the end of the day, I get to ask questions for a living. Really, I can ask whatever question I want, as long as I ask and address the questions properly, no one will question what I do.” Perhaps more importantly, Martin also mentioned that he gets to work with incredible young scientists and that seeing them grow as scientists and people and then move on to their own career is the most rewarding aspect of this job. “I’ve been incredibly lucky to work with some outstanding students who have taught me as much as I have taught them. They’re the reason I love doing what I do so much.”

So, “If you love to ask questions, you are curious, and you are willing to go the extra mile, this is the perfect career for you. Always do good science and follow the data”.