I bet you can remember a few times when you were young and someone told you: “go wash your hands before you eat”. I also bet you can remember the last time someone (or something) informed you to wash your hands before you enter the grocery store of after leaving public transportation. But do you know who was the first one that told doctors to wash their hands between doing an autopsy and treating a pregnant woman?

If you are laughing right now, I don’t blame you. This extremely trivial concept was not so trivial back in the 19th century. Isn’t it crazy that today, after we touch a door handle we feel the need of washing our hands, but back then, doctors did not think it was necessary to disinfect their hands after performing an autopsy?

One of the beauties of scientific research is the ability to design and perform the correct experiments to prove (or disprove) an idea. To have results that are so compelling that we can’t believe how it was possible for people, at some point in time, to have considered otherwise. Today, I will share with you the Lessons from Ignaz Semmelweis, a physician-scientist whose ideas and discoveries confronted the beliefs of science in his time.

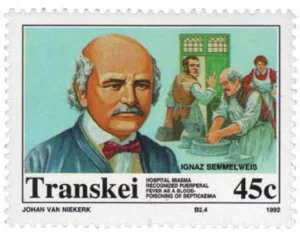

A stamp showing Semmelweis issued in Transkei in 1992. From Ataman et al. Puereperal fever with stamps. J Turkish-German Gynecol Assoc 2013; 14: 35-9

This is the first post from a new series in the ImmunoThoughts Blog, which I call “Lessons from…”. You all know how much I like to hear, learn and get tips from scientists, however, in some cases, interviewing my desired guest would be impossible (such as today’s guest, who was born in 1818). Therefore, I decided to create the “Lessons from…” ImmunoThoughts series to share with you the history and findings of some of my favourite scientists.

Two clinics, one crucial difference

Semmelweis was born on July 1, 1818, in Tabán (part of present Budapest), Hungary. After receiving his doctorate degree in medicine in 1844, he became a gynecologist and held the position as an assistant to Professor Johann Klein at the Medical School of Vienna. His role included taking care of patients, helping in difficult deliveries and performing post-mortem (autopsy) examinations.

During this time, Semmelweis became particularly interested in understanding the causes of “puerperal fever” (also known as childbed fever), which was described as an acute febrile illness that resulted in the death of many women during postpartum. Semmelweis worked in a maternity hospital which was divided into two clinics. Although the two clinics appeared largely identical, the mortality rate between clinic one and clinic two was far from similar.

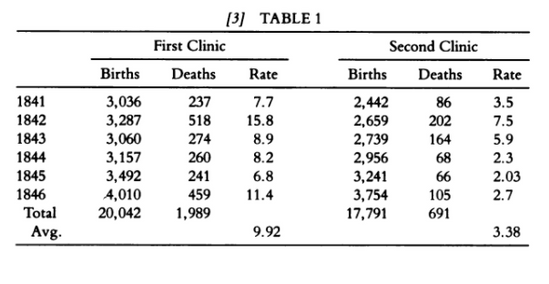

From “The Etiology, Concept and Prophylaxis of Childbed Fever” by Ignaz Semmelweis

The first clinic was made of obstetrician students and had a mortality rate of ~10%, while the second one was made of midwives and had a ~3% mortality rate. Semmelweis could not understand why such discrepancy existed, but he decided to analyze every single variable to determine the cause of such difference.

When I say that he analyzed EVERY single variable, I meant it. Reading his translated published work, one can see that Semmelweis was extremely meticulous in trying to figure out every single possible difference between clinic one and clinic two.

He started with the basics, analyzing whether procedures were done exactly the same between the two clinics. But after that, he went as deep as considering the difference in “atmospheric influences”, room crowdedness, air ventilation and even religious practice by analyzing the route taken by the priest to reach the ill patient.

Semmelweis’ prepared mind

The clue that would lead to Semmelweis’s “Eureka moment” came from a tragic event that happened to Kolletschka, a professor of forensic medicine. Kolletschka had his finger pricked by one of his students’ knife, a knife that was just used to perform an autopsy. Kollestchka became very sick and did not survive this traumatic event. Following his post-mortem examination, however, Semmelweis noticed something intriguing.

Here is where a prepared mind shines. In my view, a scientist is someone that can connect the dots and design hypothesis based on an event that everyone else sees, but overlooks. “On this excited condition I could see clearly that the disease from which Kolletschka died was identical to that from which so many hundreds maternity patients had also died”, writes Semmelweis (1).

Semmelweis suggested that the reason for the high mortality rate in clinic one was due to students having “cadaverous particles” in their hands, which could then be transferred to their patients during an examination. Semmelweis noted that “because of the anatomical orientation of the Viennese medical school, professors, assistants and students have frequent opportunity to contact cadavers. Ordinary washing with soap is not sufficient to remove all adhering cadaverous particles” (1). Therefore, Semmelweis had finally found the difference he was looking for, as midwives from clinic two did not perform autopsies.

“Father of infection control”

With that in mind, Semmelweis instituted a policy in which students and professors had to wash their hands with chlorinated lime between performing an autopsy and delivering a baby. In his mind, this action would be able to remove the “cadaverous particles” preventing it from reaching the patients. This policy decreased the mortality rate of clinic one by 90%, bringing the rate to be even lower than that of clinic two.

Beautiful, right? Now, you must be thinking that everyone was happy and pleased with such an amazing discovery. Unfortunately, not. In fact, Semmelweis’s ideas were not fully accepted or implemented until years after his death.

If you are mad with this reaction (I certainly was), try to put yourself in the shoes (and mind) of people living in the mid 19th century. Today we know that microorganisms cause diseases and that we should wash our hands to prevent contamination. But back then, people were convinced that diseases were caused by an imbalance of the “four humors”.

Briefly, it was believed that our body was made of four substances and that unfavourable atmospheric-cosmic-terrestrial influences could lead to their imbalance, ultimately causing diseases. In other words, having “cadaverous particles” in your hands was certainly not one of the reasons in which disease would occur.

Translated by K Codell Carter.

Ebook accessed via McGill University Library.

Although Semmelweis published his main work in 1861, his ideas were rejects, and even taken as an insult from doctors of his time. It was suggested that Semmelweis’ claims lacked any scientific basis, and therefore his practices were not further implemented.

Later in 1861, Semmelweis started to suffer from various nervous complaints, he became confused and agitated. Semmelweis was diagnosed as insane and, unfortunately, died two weeks following his admission to an asylum in Vienna.

Due to his inability to live in a time in which people would accept, and implement, his views in order to decrease the mortality rate during delivery, Semmelweis confessed that his “(…) death will nevertheless be brightened by the conviction that sooner or later this time will inevitably arrive” (1). Semmelweis marvellous work and critical thinking have taught us a lot about the principles of infection control and should be treasured, even more deeply, in today’s time.

References

(1) Semmelweis IP. The etiology, concept, and prophylaxis of childbed fever. Translated by Carter K Codell. Madison, Wis.: University of Wisconsin Press, 1983.

(2) Ataman et al. Puereperal fever with stamps. J Turkish-German Gynecol Assoc 2013; 14: 35-9

(3) Daniels IR. Historical perspectives on health. Semmelweis: a lesson to relearn? J R Soc Promot Health1998; 118: 367-70.