Two weeks ago I did a road trip with my (now) fiancé and our beautiful dog. We visited cities in New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island and Nova Scotia. We had an amazing time, but as soon as we got home there were a million chores to do (unpacking, laundry, groceries, etc). I was so tired and just wanted to take a long nap, but then I started to think about our immune system (shocking!). Does our internal mechanism of defence ever “get tired”? And the answer is…

Not so straightforward as we hoped for. Nevertheless, today I will tell you about what happens when our T cells get exhausted! Wait, Stefanie… are you telling me that my T cells, the ones you say are the best cells in the world (personal bias added to this sentence), can get exhausted? Yes! And although in many cases this is very bad for our health, I will also tell you why we think that “not doing the chores when tired” might have an underlying rationale. As always, get ready to be amazed by the beauty of our immune system.

Armed and ready to fight

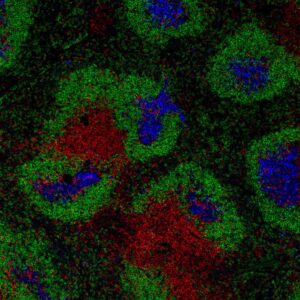

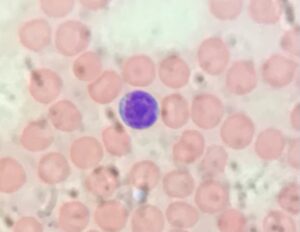

In order to understand why T cells get exhausted, we first need to go back and review what happens when they are working well. Let’s remember that T cells are part of our adaptive immune system and great at helping us fight infection and cancer. In order to do so, our T cells recognize small pieces of proteins from foreign invaders (such as a piece of a virus or a piece of bacteria), as well as pieces of mutated proteins (such as proteins from cancer cells).

The recognition occurs via a receptor, called the T cell receptor (TCR). The interaction between the TCR with its target protein provides one of the signals required to activate the T cell which together will pretty much tell our T cells “get ready to fight!”

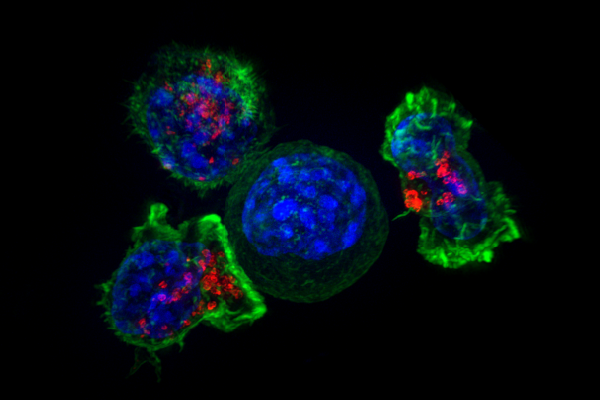

In order to win this battle, they have to think about quantity and quality. One T cell might not do much damage, so, as soon as a T cell is activated it will start to proliferate. We call this the expansion phase. This will ensure that inside our body we will have higher numbers of T cells that are specific to the threat being present (whether is a virus, a bacteria, or a cancerous cell).

But an increase in numbers is not the only thing, they also need their tools. Think about an army of soldiers without any equipment to attack their enemy… not very good, right? So, T cells will acquire effector functions, meaning that they will start to produce important proteins (their tools to attack) to be able to fight the current danger.

Fluorescence microscopy image of T cells surrounding a cancer cell (center). Credit: Alex Ritter, Jennifer Lippincott Schwartz and Gillian Griffiths, National Institutes of Health

After this expansion phase, our T cells will start to die. Around 90 to 95% of all the T cells that have just expand will die in this contraction phase. Why? Well, they have already done their job, and we don’t want fully armed killing machines just roaming around our bodies. Although T cells are amazing (bias added again) they can sometimes make mistakes.

Get ready to fight… again and again and again

What if, for some reason, our T cells were unable to remove the threat mentioned above, would they ever get “tired” of fighting? Great question, but before I answer it I just want to make sure that you understand that I’m using the term “tired” to hopefully make the concept more palpable. The term T cell exhaustion is what is actually used by scientists.

Ok, so imagine that you are cleaning your room using a mop. You finish cleaning one side and you turn around to see another dirty area. So, you go there and mop it. As you turn around, another dirty area! You mop it again, and again, and again. Every time you see the mess, you use all your “effector functions” (in this case your mopping abilities) to clear the issue. You see where I am going with this, right? You will get tired at some point.

And this is what happens with our T cells when they are unable to clear our infection. In this case, we call it a chronic infection, which means that the infection is persistent, and thus we have persistent antigen (the little piece of protein from virus/bacteria/cancer) that can activate our T cells.

Just like me, that decided to not perform my chores after arriving from my trip, exhausted T cells will also decrease their effector function when antigen is constantly being present. This means that they have a lower ability to produce important effector proteins (such as cytokines).

No chores when I’m tired, it is for your own good

Wait, Stefanie… are you telling me that at the moment I need my T cells the most (i.e. during a persistent infection or cancer), they just “decide” to get exhausted? WAIT UP, before we start judging our T cells for getting exhausted I want you to change your mindset for a second and think about why!

We had a huge amount of time to evolve, and at some point during this timeline, a mechanism that decreases the function of T cells during chronic stimulation was selected and passed along from our early, EARLY, ancestors all to way to us. This could possibly mean that having this T cell exhaustion mechanism is a good thing, at least in some cases.

As previously mentioned, T cells have amazing effector functions that lead to the removal of unhealthy cells, however, our T cells can, unfortunately, be inaccurate. Sometimes, our T cells can mistakenly attack our own healthy cells leading to the development of autoimmune diseases.

Therefore, scientists believe that T cell exhaustion is a mechanism that, although does not help clear the infection/cancer present, prevents possible collateral damage caused by our fully activated T cells staying in our bodies for too long. By acquiring a mechanism that decreases their function during constant stimulation our immune system could prevent the development of immune pathologies (such as autoimmune diseases). Cool, right?!

What’s next?

There is a LOT to talk about when we think about T cell exhaustion, but I wanted to devote this post to introduce the concept to you, and we will build on it on the following ones. Many amazing scientists are devoting their entire careers to study this process and I will try to bring a feel of their findings to you very soon.

Questions such as can we revert T cell exhaustion to help treat cancer? or, can we take advantage of such mechanisms to treat conditions in which T cells are overly activated, such as in autoimmune diseases? might be popping in your head right now. If these (or any other questions) are flooding your brain, write them in the comment section below I would be thrilled to know your thoughts!

So, next time you are tired and someone asks you to do any chores, you can say you are exhausted, and thus decreasing your effector functions to prevent any collateral damage. Just please, don’t tell them it was me that told you to say that!

Keep asking questions and seeking answers… and please go get the COVID vaccine if you haven’t done it yet.

From your immunologist – in training,

Stefanie Valbon

PS: Thank you so much for those that sent me messages saying they miss the blog posts, you are truly helping me avoid my impostor syndrome and pushing myself to continue doing what I love!