It is my pleasure to introduce you to Dr. Lisa Osborne. I was very fortunate to meet Dr. Osborne last year at the Canadian Society for Immunology Meeting. I can’t emphasize enough how great our meeting was. I was especially amazed by Dr. Osborne’s attention to the students. She not only took the time to ask each of us questions about ourselves and our research, but she also provided us with many tips based on our future goals.

The day that I met Dr. Osborne I was extremely nervous. It was the first time I was presenting my research to such a big audience. I won’t lie, I was freaking out! Without knowing me too well, Dr. Osborne paid special attention to my feelings, giving me many insights which were essential to keep me calm. I don’t know whether Dr. Osborne realized how much impact she had on me that day.

There was no doubt in my mind that I had to try to interview Dr. Osborne for the blog, as I believe that featuring such an amazing leader is crucial. I was quite lucky that Dr. Osborne agreed with this interview, where she talked about her pathway to becoming a scientist, her research projects, tips to young scientists as well as some of the challenges of being a woman in STEM. I hope you enjoy this interview as much as I did.

Thank you so much Dr. Osborne for taking the time to talk to me, and for all your amazing insights.

“I didn’t know that being a scientist was an option”

Like many of us, Dr. Osborne didn’t have a clear career path in mind from a young age. Being the first college student of her family, Dr. Osborne started her journey doing a co-op BSc in Microbiology at the University of Victoria. The co-op (co-operative education) is a program in which students have the chance to work in their field of interest during their degree. Although Dr. Osborne does not remember exactly what her motivation was to follow this path, she remembers being very intrigued about the possibility of working at the lab. So, she decided she needed to experience it.

During her first internship at the lab, she remembers that her supervisors Drs Christine DiDinato (now at Northwestern University) and Rashmi Kothary (Ottawa Hospital Research Institute) “had really high expectations, and I didn’t know any better. So, I just tried to meet them”. Near the end of the semester, her professor told her that if he was searching for a PhD student, he would happily accept her into his lab. Dr. Osborne told me how surprised she was with that comment. “He doesn’t think I’m terrible at this. Well, that is cool!”

During her second internship, her supervisor Dr Robert Burke (UVic) encouraged her to apply for graduate school. However, she admitted that “that was not something on my radar. During my undergraduate, I would look up to the graduate students and all I could think was how incredibly smart they were. There was no way I could get to where they were”. She told me that being encouraged by someone that she respected so much to pursue graduate school was incredible.

Dr. Osborne then joined Dr. Ninan Abraham at the University of British Columbia (UBC) with the goal of doing a Master’s degree. “I wanted to go in and out and get my master’s degree (…) because that was what I thought I would top up at”. However, she remembers that during her MSc “there were always more questions to ask and more things to be done. Ninan encouraged me to stay and do the transition to a PhD. And, towards the end, he also encouraged me to do a postdoc”.

Dr. Osborne recounted that at that time she had doubts anyone would want to hire her. So, she made a list. In that list, she wrote the name of every single professor she would like to work with during her postdoc. She admitted to me that she was very ambitious writing this list, and at the very top she wrote Dr. David Artis from the University of Pennsylvania. For her surprise… although I don’t think it was no one else’s surprise, Dr. Artis accepted her. Everyone from the lab “told me that I was smart enough and that I was driven enough”

“The theme, that came out from all of this is that I had an incredible case of impostor syndrome. I didn’t think I belonged in academia”. However, she told me that through every single step, there was always someone advocating and encouraging her to continue. Dr. Osborne told me that every time she doubted herself she “basically just started to have more faith in their views than on my own”.

Dr. Osborne also ensured to emphasized how grateful she is for the support of all her mentors and friends she met along the way. She sincerely values the opportunity to do the same for someone else during their career. “If there’s someone who needs a boost to meet their potential, I don’t want to overlook it”. Dr. Osborne is now an Assistant Professor at the Department of Microbiology and Immunology at UBC.

The good and… the great of becoming a professor

Many of us have the goal of becoming a professor, however, we hear a lot about how demanding this job can be. Hence, I decided to ask Dr. Osborne two questions: First, I wanted to know what was one thing that scared her the most about becoming a professor. Second, about the driving force for her to follow this pathway. I was actually most intrigued to know whether these two points were still as scary/rewarding as she once first thought they would.

When Dr. Osborne was in graduate school, she told her peers that she didn’t want to become a professor because “I didn’t want to have people’s careers rely on my ability to secure money”. Although Dr. Osborne admits that this is still a huge concern, she actually quite enjoys the grant writing process. She explains that writing a grant is very hard, physically and emotionally, but it is extremely rewarding when you read the final piece and think “this is the best idea ever!”

Dr. Osborne explained to me that as a PI (primary investigator/the professor of the lab) there are so many things to do. Yes, you have to take care of your students, but there is way more to that. There’s administration work, teaching and so many emails to write. With all of that, keeping up on the literature for multiple projects is hard. However, during grant writing, you get to go deep and read any new research that you had missed. “You get yourself back into really understanding where your field is”. Dr. Osborne confesses that it is a very hard process but is also a privilege to get money to answer questions you think are truly important.

On the other hand, “the thing that I always thought would be great about this job, and is actually even better than I thought it would be, is interacting with students”. She remembers that “there was a moment where I was teaching a student the steps to perform flow cytometry and I thought ‘I have done this so many times!’…but this is what I signed up for”.

She told me that there will always be a new student that won’t know how to perform a technique. However, by the end of their degree, they will be able to do this, and others, in their sleep. She confessed that it is extremely gratifying when a student comes into her office and tells her exactly what experiments he/she needs to do. “There you go, you are becoming a scientist. You are doing it!”. Her favourite part is when a student comes into her office and asks “what about this?”. I swear I could see Dr. Osborne’s eyes shining a bit brighter as she explains what she answers in this situation: “Yes, what about it?”

Your friendly microorganisms

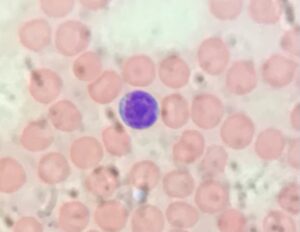

We have been talking a lot about pathogens in the blog, which are microorganisms that cause diseases. But when asking about her research, Dr. Osborne reminded me that we are also covered by microorganisms that are not harmful. These are actually extremely important for our health. In their absence, our immune system doesn’t develop properly and we don’t metabolize nutrients well. Without these “friendly” microorganisms many parts of our bodies can be affected.

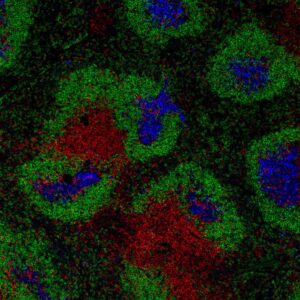

Most researchers focus on the bacteria side, and what they do to help us. But, Dr. Osborne goes beyond. Her research focuses on studying viruses and worms that are present in our gut. Dr. Osborne wants to understand the immune pathways which are affected in the presence or absence of these specific microorganisms.

She told me that she is fascinated by helminth therapy. This is an experimental type of immunotherapy in which patients with autoimmune disorders are infected with a worm in the hope of decreasing their symptoms. She wants to be clear that clinical trial data doesn’t support this kind of treatment (please don’t try this at home), but she (and others) are still investigating. “I think there is still space for further understanding about whether or not helminth immunotherapy could be helpful”.

Dr. Osborne explained that “we can see in mouse models of many diseases, such as allergy or Multiple Sclerosis, that if you give the worm before giving the disease, there is a delay, decreased severity, or even prevention of the onset of the disease”. The difference, however, is that helminth immunotherapy is provided to people that already have developed the disease. “And that is one thing I want to try to address: how late is too late?”

Dr. Osborne told me that she is a basic scientist, and she is fascinated with the idea of understanding how exactly things work. However, she also “absolutely hopes that the work we do will contribute to a translational impact”.

“Believe those who believe in you, blow past those who might try to hold you back!”

I have to admit that one of my favourite parts of these interviews, is asking professors for tips for young scientists (as I’m one myself!). I think it is extremely powerful to be able to receive insights from those that have reached what we aim to reach. Hence, I decided to ask Dr. Osborne a few questions about her journey. I first wanted her input on the challenges of transitioning from undergraduate to graduate school.

“At some point, you have to realize that you are no longer looking for the right answer, you are looking for a new answer. In high school and undergrad, you are taking the information and showing that you can incorporate it. There is a right answer. But the further along you go, there is no one to tell you that you are right. So, you have to be willing to take risks and you have to be willing to be wrong.”

Dr. Osborne then emphasized that unfortunately during this journey many people feel out of place. Some, like her, are first-generation college students and that can make you feel like you don’t belong. She stated that everyone has to think about ways to create a more inclusive environment for students. “I think that interviewing professors and asking them about their pathway is amazing because there is no right or direct route”.

“It is also very important to continue to show that doing a PhD, postdoc and becoming a PI is not the only route for success after graduate school”. She mentioned that there are many other pathways for people that like science but don’t want to become a professor. “Do whatever you have to do to use your talents, rather than being miserable doing something that somebody else thinks you should be doing”.

“My biggest advice for young scientists is: Just keep going. If you like what you are doing, and there is no one standing on your way, just keep going. And if there is someone standing in your way, just ask yourself ‘Why? Is it to do with you or with them?’”

Well, I’m a woman…

One thing that I noticed as I started to think about becoming a scientist, was that all the mentors of my professor were males. Don’t get me wrong, they are all amazing, but I never got the sense that ‘I looked like them’. For me, this view changed once I started to attend conferences. I didn’t notice at first, but it was always the same. As soon as I heard an amazing talk from a female scientist, my brain somehow would trigger a switch and I would think ‘Stefanie, maybe you could actually be like her’.

It is funny how you don’t realize you are missing someone like you, until you do. But things change when you see that person doing something you didn’t think you could. With that thought in mind, I decided to open up and tell Dr. Osborne how I felt. I wondered whether she went through any trouble to get to where she was for the sole reason of being a woman.

Dr. Osborne told me that during her postdoc she noticed something wrong happening during group meetings. When she, or other women in the room, would ask a question about the talk being presented, it would just fall flat. Two minutes later, a man would put his hand up and rephrase the EXACT same question like it was his own idea. Suddenly the room would go like “wow, isn’t that so smart!” Dr. Osborne told me that as soon as she noticed that this was happening, she couldn’t unnotice it.

She then decided to tell one of her male friends about this problem, and she was shocked by his reaction. He could not actually believe that such a thing was happening, even though he was part of the problem. She recognized that they were not doing in a malicious way, they were just blind to it. And “if you don’t notice you have a bad behaviour you can’t change it”.

And that is why Dr. Osborne advocates that we should all pay attention to these patterns. It is important for us to not let this happen anymore. “When you are on these group meetings and you notice a woman making a comment that you think is important but it doesn’t actually go anywhere, you can say: ‘I would like to echo her idea’. Bring it back and give credit for it. Tell the guys you work with for them to keep an eye on it. For them to echo your ideas and give you credit for it”. We all have to work together. Remember, the first step is noticing the bad behaviour and then changing, forever!